It’s early May in Hoover, Ala., and there are Southeastern Conference banners hanging from the streetlights. If towns talk via what they choose to promote, it could seem like a strange thing to say to an outsider. Unless you know that the SEC holds its annual media days here in the suburbs south of Birmingham, it might just look like an odd bit of allegiance to a conference fostered through football. Even if you do know, that event is more than two months away — it’s a safe bet that Chicago hasn’t put up its Big Ten banners yet — so the message conveyed is the same, and that’s probably not a coincidence.

This is the crossroads of football and friendliness. You can find both in abundance elsewhere, but they seem to be at their strongest, together, in the South. People here prize conversation as much as football, so every chat, no matter how short or how it starts, eventually arrives at the subject everyone is thinking about always — football.

It’s also one of the most talent-rich parts of the country when it comes to turning out young gridiron heroes, though it’s hard to tell if there’s so much talent because people care about the game so much or if people care so much because there’s so much talent. Either way, this is where Ameer Abdullah grew up.

It’s a rainy Friday night and he’s walking through a parking lot to a members-only gym in a strip mall. He’s wearing his team-issued workout gear. His oldest brother, Muhammad, is in an Oxford shirt and slacks. Work clothes. He came straight from his downtown office, where he works as an attorney at law. This is their routine in the rare moments when Ameer can get home for a few weeks.

In the most literal sense, Muhammad might be the most-powerful lawyer in Birmingham. After some stretching, the two brothers start bench pressing. It isn’t long before Muhammad is putting up 315 pounds pretty easily.

Nebraska’s all-conference running back isn’t ashamed to admit that his brother, once a cornerback at Alabama State and 16 years his senior, is the stronger one. It’s valuable, actually. There can’t be too many Heisman contenders who have this. A mentor? Sure. But one who can go pound-for-pound with the athlete in his prime? One who asks a lot of the athlete only because it was what he asked, and still asks, of himself?

They move to the incline and put four 10-pound weights on each side of the bar. Muhammad goes first. Ten reps of 125 pounds, rack the bar just long enough for two spotters to remove one of the weights from each side, then 10 more, all the way down until the bar is empty. Do 20 reps with just the bar. Then start adding the weights back on, 10-pounds each side, all the way back up to 125. It’s 100 reps total in just a few minutes. Both make it through, but it’s brutally tough.

An older man, 50s maybe, is watching this while working out with a trainer nearby. He knows Muhammad and knows of Ameer. He speaks in a drawl that seems thickened by generations in the South, but that can’t be true. He looks as if he’s from somewhere else. He is. He played some baseball at Samford University, but it never went beyond that because, as he explains it: “Have you ever seen a Palestinian in the major leagues?”

This man has some questions for Ameer. He asks about who Nebraska faces to start the season and who will be the toughest opponent in non-conference play. He’s an Auburn fan so it’s all just a prelude to what he really wants to ask.

“Why didn’t you go to Auburn?”

“Because I didn’t want to play safety.”

It’s a quick cut, which might be Ameer’s best quality on the field but it works just as well here because there’s nothing left to be said, no follow-up. He’s already by you.

They move on to push-ups. Muhammad does one, holds the press until Ameer does one, then does two and on they go in alternating bursts until each reaches 10. A few minutes later Muhammad says that the man who asked is “one of the most powerful lawyers in the city.”

“It’s like that all the time down here,” Ameer says. “Why didn’t you go to Auburn? Why didn’t you go to Alabama?”

Those particular questions are asked only in hindsight, three years and nearly 3,000 yards into his college career.

“He was always very physical. Ameer never realized he was not equal to his older brothers.” — Aisha Abdullah

Aisha Abdullah got a call once while Ameer was still in daycare. The provider wanted her to know that her son liked to jump off things. A lot.

“He was always very physical,” Aisha says. “Ameer never realized he was not equal to his older brothers.”

It wasn’t a surprise. The Abdullahs had a pretty clear line of athletic success by then, but Aisha, who works for the Head Start Program in nearby Bessemer, prized education more than the rambunctiousness of young boys. She told all of her children to get a bachelor’s degree for her and then “everything else is yours.” When Ameer graduates in December, all nine of the Abdullah children will have fulfilled their mother’s request and earned at least one degree. His diploma will go on a wall full of them. This is a family of high achievers.

Halimah set the tone. The oldest daughter earned two degrees and is a writer and producer for CNN. After his playing career, Muhammad earned a law degree from Alabama. Sisters Aisha and Kareemah both work for major telecom companies, Ruqayyah for one of the largest banks in the U.S. Khadija went to law school at Arkansas, then returned home to become the executive director of the Alabama branch of Teach for America. Madinah, the sibling Ameer calls the best athlete in the family, was the 2009 SWAC Volleyball Tournament MVP for Alabama A&M. Kareem, the second-youngest brother, recently graduated from Auburn.

It’s an impressive precedent for a youngest child. There could either be immense pressure to succeed, or the dividends of hard work could appear so tangible as to seem like the natural order of things. Ameer says it’s the latter.

Still, it can be tough to stand out in a family like that, but Ameer’s father, Kareem, noticed a difference in his youngest son right away.

“Ameer was very perceptive,” he says. “He didn’t talk as much as the others. He was just always observing.”

Kareem also saw that Ameer needed athletics. What was at first just a diversion in Aisha’s eyes was essential in Kareem’s view. So Ameer played baseball, basketball and boxed briefly. But it was football that really took hold.

He started playing in pick-up games with his brother, Kareem, who was three years older. That continued in the youth football leagues, where the smaller, younger running back found a way to gain an advantage.

“He studied all the positions,” his father says. “He knew the blocking schemes, knew where every player should be.”

Thanks to that knowledge, Ameer moved around a lot as a young player. He played some quarterback, wide receiver, corner and safety, whatever the team needed, but he always knew he was a running back.

Homewood High School is smaller than most of the football powers surrounding Birmingham. Kareem and Aisha moved out there for the quality of the education and so did a lot of others. The Patriots had won five state titles playing 5A football, but shortly before Ameer enrolled, Homewood grew so large it had to move up to the state’s largest classification.

“We kiddingly, as coaches, called it the SEC West,” former Homewood coach Dickey Wright says. “That’s what it felt like we were going up against every night.”

Over 30 years as an assistant and head coach at Homewood, Wright had supplied those SEC West schools and others with his share of recruits. But Homewood was the second smallest school in 6A and success became something of a numbers game every week. Schools like Hoover, Vestavia Hills, and Mountain Brook didn’t just have more players, they typically had a handful of college prospects each season. The Patriots had two — Ameer and his friend, a slight wide receiver by the name of Aaron Earnest.

Wright didn’t see a future Heisman candidate in Ameer right away. He simply saw a dedicated, but small, player who could squat a tremendous amount of weight.

“The thing we were concerned about was would he be big enough to take the pounding in our particular league,” Wright says.

It wasn’t an uncommon question, but Ameer finally settled in the backfield full-time as a junior, rushing for 1,045 yards and 14 touchdowns. Then he hit the camp circuit.

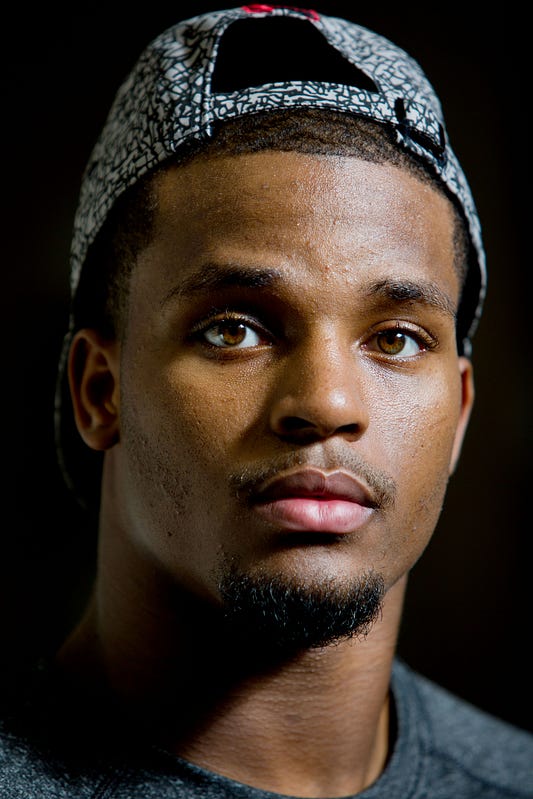

Ameer looks at a family photo at his family’s home.

Ameer enjoys time with his family, including, from left, his sister Aisha Carmichael, his 18-month-old nephew Eli Carmichael, his sister Ruqayyah McPherson, his brother-in-law John Carmichael and his sister Kahadijah Abdullah at the family’s home.

He dominated at a Nike camp in Baton Rouge following his junior season, taking home camp-MVP honors at running back. He beat out Jeremy Hill, who committed that weekend to play running back at LSU. A month later, at a similar camp in Tuscaloosa, it was the same result. Ameer was named MVP of a running-backs group that included Demetrius Hart, the nation’s top-ranked high school back. Alabama signed him.

Scholarship offers started to trickle in after that. Vanderbilt and Texas A&M were first. South Carolina and Texas Tech weren’t far behind. As Ameer went on to rush for for 1,795 yards and 24 touchdowns as a senior in 2010, more offers came. He visited Tennessee during the season and, when Lane Kiffin bolted Knoxville for USC, Ameer suddenly had an offer to play for the Trojans, too.

But there was still the perception that Ameer wasn’t built to be an every-down back. He was good, clearly, but something else. The Birmingham Newsused a Christmas-themed layout for its All-Metro team that year, with the players’ head shots laid out as ornaments on a tree. The star at the top, player of the year, was Leeds defensive back Jonathan Rose. He’s a cornerback at Nebraska now, after spending one season at Auburn. One of the quarterbacks honored was 2013 Heisman winner Jameis Winston, then a junior. Ameer made it as an “athlete.” Unless you’re a close follower of SWAC football, you haven’t heard of the three guys listed that year at running back.

Late that December, Ameer was selected to play in the Offense-Defense Bowl in Myrtle Beach, S.C., an all-star game for high school seniors. Despite not playing the position for more than a few snaps in 2010, he had to play cornerback for the East. He had eight tackles and picked off future Texas starting quarterback David Ash twice. A writer for Rivals.com said Ameer had the best cover skills of any player there. The other defensive backs on his team signed with Alabama, Ohio State, Ole Miss, Florida and Mississippi State.

The notion that Nebraska landed Ameer because it was one of the only schools promising a shot at running back isn’t entirely accurate. Nebraska landed Ameer because it didn’t promise anything, actually.

Offensive coordinator Tim Beck was the first to visit the Abdullah household, but it wasn’t until early January. The Huskers were a latecomer. Beck laid out the situation. Nebraska already had Aaron Green, a 5-star prospect out of Texas, committed in that class, and there was a chance that Braylon Heard, an All-Ohio running back who had committed a year earlier but failed to qualify, would be a true freshman in 2011, as well. If Ameer was OK with that, he was welcome to come to Lincoln for a visit.

He went two weeks later, convincing the Huskers to take a look at his friend, Aaron Earnest, who went on the visit, too. Nebraska didn’t offer Earnest. Instead he accepted a track scholarship to LSU and, in 2013, was an All-American sprinter.

Ameer left Lincoln still undecided. Kareem wasn’t able to make the trip, and Ameer wanted to talk with his father about the decision. But Kareem already had full confidence in his son.

“He makes good decisions,” Kareem says. “The tendency of a father is to try to help. Hearing Ameer’s maturity, I didn’t want to slow him down.” Ameer called up Beck and told him he wanted to be a Cornhusker.

Auburn had slow-played things to that point. The coaches knew Ameer was a Tigers fan and that his brother went to school there, but when he pledged to Nebraska, they finally realized they might lose one of the state’s top-20 players. Gus Malzahn, then the Tigers’ offensive coordinator, stopped by and got Ameer to seriously consider a visit. Associate head coach Trooper Taylor came by a few days later and told him that if he really wanted to get on the field early, safety might be a better bet as the Tigers already had Tre Mason verbally committed at running back.

“That didn’t sit right with me,” Ameer says. He stopped thinking about Auburn and stuck with Nebraska. Throughout the whole recruiting process, Bo Pelini was the only head coach to visit the Abdullah home.

“He was very observant,” Kareem says, using the same word he used to describe his son at a young age. Ameer recalls that there was little small talk. Most importantly, Pelini didn’t promise anything.

Barry Sanders. If he’s not a running back’s favorite player, you wonder why not. He was fast, strong and elusive, a Heisman winner and an NFL Hall-of-Famer who made the Pro Bowl in each of his 10 years in the league. He excelled at every facet of being a running back at every level he played. And he was 5-foot-8, 200 pounds.

Ameer is listed at 5-9, 195 heading into his senior season, but it’s not the size similarity that makes Sanders his favorite. Ameer believes they share a career trajectory.

Nebraska running backs coach Ron Brown, who coached against Sanders’ Oklahoma State teams, highlighted the similarity early in Ameer’s career. The Cowboys had All-American Thurman Thomas for Sanders’ freshman and sophomore seasons. No chance of starting. So Sanders excelled on special teams, leading the nation with more than 30 yards per kickoff return as a sophomore.

Down 28-0 headed into the fourth quarter against Nebraska that year, Oklahoma State removed Thomas after he had rushed for 7 yards on nine carries and inserted Sanders. The sophomore went for 60 yards on seven carries and Brown knew he was going to be tough to handle in years to come. And he was. The next season in Lincoln, Sanders exploded for 189 yards and four touchdowns in a 63-42 loss. After rushing for barely more than 900 yards in his first two seasons, Sanders ran for 2,628 as a junior, in 11 games, an NCAA record that still stands.

Like Sanders, Ameer arrived in Lincoln in 2011 with no clear path to playing time. Fellow freshmen Green and Heard were more-heralded, and Nebraska already had junior Rex Burkhead coming off a 900-yard season while splitting time with senior Roy Helu Jr.

So Ameer excelled on special teams, setting a school record with 211 kickoff-return yards against Fresno State in just his second game, including a 100-yard touchdown return that broke the game open in the fourth quarter. He earned the most carries of the freshmen backs that season. Green transferred to TCU.

The following season was expected to be the showcase season for Burkhead, but the senior got hurt in the season-opener and never fully recovered. Thrust into a starting role, Ameer led the team with 1,137 rushing yards. Heard transferred to Kentucky.

Last year, Nebraska was expected to be an offensive juggernaut. Instead, starting quarterback Taylor Martinez missed eight games, and Ameer had to shoulder the load, rushing for 1,690 yards and earning first-team All-Big Ten honors.

That strong junior season left Ameer with a decision to make this past winter. This is no country for young running backs. The position has been devalued at the pro level, partly because it’s a passing league now more than ever and partly because the average career for an NFL player is five years, three for a running back. Most backs good enough to leave early do. If it’s going to shorten your career, better to get beat on while getting paid than for free.

Ameer got help from his coaches and an outside consultant, who did their best to determine where he might be selected. He did his own research, too, comparing his stats and measurables to those of the other backs coming out. Muhammad filed his paperwork with the NFL to get certified as a contract advisor if he was needed. Kareem says they didn’t need to talk about the decision. “He makes good decisions.”

Photo by Alyssa Schukar

Ameer decided to stay, announcing his decision in an elegantly worded statement on Jan. 9. “I have come to realize that life is bigger than football, and that my chances of long-term success in life will be greatly enhanced by completing my college education,” he wrote.

“It’s hard for young athletes to have an accurate view of that short window of life,” Aisha says. “Ameer did.”

Ask the running back what he wants to improve upon before his senior year and he makes another quick cut. He has a question of his own: “As a person or as a player?”

Seated on a couch next to this father in the family’s home in Bessemer, Ameer rattles off all of the things his family members have already said he’s good at — compassion, maturity, thoughtfulness — but he sees room to improve. There always is.

He also wants to be a more physical runner. He needs to fumble less. He gets tired too easily. Mostly, he doesn’t want to be known as a “speed back.”

“It gets under my skin. I don’t want anyone to say, ‘We need a speed back, let’s go get Ameer.’”

Back to the Friday night in the strip-mall gym. It also happens to be the second night of the 2014 NFL Draft. It’s easy to see the juxtaposition here. With a different decision, Ameer could have been watching the draft with his big, supportive family — thinkers, athletes and achievers, all of them — waiting to find out where life was going to take him. Instead he’s here, trying to keep up with his oldest brother.

“Miami doesn’t care what you could’ve been doing tonight,” Muhammad says as the pair takes turns doing dips with a 10-pound kettle ball chained around their waists. Nebraska plays the Hurricanes in week three this season. Miami has its own highly regarded back, Duke Johnson. He’s 5-9, 195 pounds and wears No. 8, too. Gotta be better than him.

Midway through the workout, the running backs finally start to come off the board. Washington’s Bishop Sankey goes first with the 54th overall pick. It’s the latest the first running back has been selected in NFL history. Next is Jeremy Hill, the back Ameer outdueled at a camp four years ago. He goes to Cincinnati.

“What about Rex?” Ameer says, more to himself than anyone else, thinking of his former teammate, who’s a second-year player fighting for carries with the Bengals.

Carlos Hyde, the other first-team All-Big Ten running back in 2013, is selected a few picks later. Then it’s Tre Mason, the running back Auburn didn’t ask to maybe think about playing some safety. Muhammad knows Ameer is better than all of them, and says so.

The brothers continue pushing each other through lifts, not because this news has served as any additional motivation but because it’s just the way they do things. If anything, the news of the further devaluation of the professional running back confirms Ameer’s decision to get his education and play his senior season. He’s already applied to graduate school. He’s interested in teaching, possibly with his sister Khadija’s Teach for America program, or going the legal route and starting a sports agency

The high-powered attorney is back. Muhammad’s description is accurate. He’s a personal-injury lawyer with billboards all over Alabama, TV commercials up and down the dial, offices in Huntsville, Birmingham, Montgomery and Mobile. He wants to talk more football because everything else is just a diversion down here. He watches the brothers’ workout from far away, out of earshot.

“Where do you think he’ll be drafted?”

It’s a question that can drive sports-talk shows for the next 10 months and fuel small talk between football fans. Hours of programming and millions of dollars in advertising are spent on questions such as this.

Brandon Vogel is the managing editor of Hail Varsity magazine. This story and photos were originally published in Hail Varsity’s 2014 football yearbook.

Alyssa Shukar is a Chicago photographer and was recently honored by World Press Photo andPictures of the Year International. She was also named the 2014 Great

Replies